On Wednesday, July 20, 2022, I stepped to the lectern in Congregation Kehillat Israel of East Lansing, Michigan, to celebrate the life of my friend Aryeh Seagull, who passed from this plane of existence a month before. Aryeh’s family asked that I speak on one of his favorite subjects, the rules of etiquette and practice which Jews believe must also be honored by non-Jews. What I hoped to accomplish was to demonstrate how seemingly simple questions about Jewish beliefs can lead to wrinkles within wrinkles, moving seamlessly through time and space, from the Bible to the Talmud to the Rambam, back and forth, motion without end.

The first question I posed to the congregation was, “When someone says that the Torah demands that non-Jews observe Jewish rules, what is your reaction?” After some interesting comments from the community, I noted that it was actually a trick question. The Torah knows nothing of Jews or non-Jews since those concepts developed long after its day. The Torah knows of Israelites and Judeans among other designations of the people living in the land. Other books of the Bible call the people “Hebrews.” But the term “Jew” developed long after the Torah was published. That means that if we are speaking one of the most ancient documents recognized by modern Judaism, we must ask whether that

document demanded any sort of behavior from the peoples who were not the recipients of the Torah according to the Torah’s own worldview.

As always, we are obligated to turn back to the sources. Before I do, let me set one issue aside. Christian theology demands that Scripture be taken seriously, and they have a doctrine which includes a quasi-legal status for this. It is the Christian claim that those who follow Christianity are the “New Israel.” As such, Christians view themselves as the inheritors of the requirements of the Torah. It would take us too far afield to discuss how Christians distinguish between rules that obligate them and those that no longer do. But I would caution my Jewish friends about this “picking and choosing” not to be too smug

about this unless you too want to consider yourself obligated to stone someone

to death. The question before us, however, is not whether Christians have somehow

replaced Jews as this “New Israel” but rather how Israelites and Jews viewed

the necessity of outsiders to obey the rules of the Torah.

Since the Bible is ill-equipped on its own to answer the question, it is natural as Jews that we turn to the foundation of the Jewish religion, the Talmud. And it is there that we will strike gold. One of the earliest documents of the rabbinic era, the Tosefta, contains the following statement (Avodah Zarah 9:4):

על שבע מצות נצטוו בני נח על הדינין ועל עבודת כוכבים ועל

גלוי עריות ועל שפיכות דמים ועל הגזל ועל אבר מן החי

The sons of Noah were given seven commandments: courts, idolatry, [blasphemy,] forbidden sexual relations, bloodshed, theft, and [consuming] the limb of a living animal.

What does the Tosefta mean by בני נח “the sons of Noah”?

This one does have a clear answer. The term ben adam (descendant of Adam)

obviously means “everyone.” But as the Torah lays out the story of the history

of people-kind, b’nei adam lacked a few permissions that would later be allowed; for example, the consumption of meat. Noah represents a kind of second Creation, because according to the account, Noah’s family are the sole survivors of the Great Flood. Therefore, just as everyone is descended from Adam and Eve, so also everyone is descended from Noah. Interestingly from the perspective of our topic, Israelites are also

b’nei No’ah, but of course the difference is that Israelites have a few hundred extra requirements!

There are questions, always questions! What exactly were the commandments given to the

descendants of Noah? The obvious place to look is Genesis 9, where Noah’s

family exit the ark:

1 God blessed Noah and his sons, and said to them, “Be fertile and increase, and fill the earth. 2 The fear and the dread of you shall be upon all the beasts of the earth and upon all the birds of the sky — everything with which the earth is astir — and upon all the fish of the sea; they are given into your hand. 3 Every creature that lives shall be yours to eat; as with the green grasses, I give you all these.

4 You must not, however, eat flesh with its life-blood in it. 5 But for your own life-blood I will require a reckoning: I will require it of every beast; of man, too, will I require a reckoning for human life, of every man for that of his fellow man! 6 Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed; for in His image did God make man.

7 Be fertile, then, and increase; abound on the earth and increase on it.” 8 And God said to Noah and to his sons with him, 9 “I now establish My covenant with you and your offspring to come, 10 and with every living thing that is with you — birds, cattle, and every wild beast as well — all that have come out of the ark, every living thing on earth. 11 I will maintain My covenant with you: never again shall all flesh be cut off by the waters of a flood, and never again shall there be a flood to destroy the earth.”

12 God further said, “This is the sign that I set for the covenant between me and you, and every living creature with you, for all ages to come. 13 I have set my bow in the clouds, and it shall serve as a sign of the covenant between me and the earth. 14 When I bring clouds over the earth, and the bow appears in the clouds, 15 I will remember my covenant

between me and you and every living creature among all flesh, so that the waters shall never again become a flood to destroy all flesh. 16 When the bow is in the clouds, I will see it and remember the everlasting covenant between God and all living creatures, all flesh that is on earth. 17 That,” God said to Noah, “shall be the sign of the covenant

that I have established between me and all flesh that is on earth.”[1]

Understand that “all flesh” must include everyone, not just Israelites. What commandments does God require of “all flesh”? Here’s my list:

1.

Be fertile and increase

2.

Every creature that lives shall be yours to eat; as with the green grasses, I give you all these.

3.

You must not, however, eat flesh with its life-blood in it. [Should this really be 3, or is it part of 2?]

4.

Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed.

I see 3 or maybe 4 rules that apply to Noah’s descendants, at least here in this most direct

passage. But how do these stack up against the rules we just learned from the Tosefta?

Rule #1 isn’t even included in the Tosefta!

Rule #2 isn’t in the Tosefta, unless you join it to #3, which is definitely there.

Rule #4 is in the Tosefta as it rules that b’nei noah are forbidden from “bloodshed.”

You can stretch rule #4 if you want to include courts of justice by arguing that it would be

hard to enforce rule #4 without them.

Now, I must do a bit of a dodge, just for the sake of our time together. Various other rules, such as the condemnation of blasphemy, are derived from other texts in the Torah–often by torturous manipulation. I’ll leave those for a different day.

Have we ever found a situation where our sources all agree about something? Are there really the same seven everywhere, and are there only seven? The Talmud, tractate

Sanhedrin, picks up the theme:

תנו רבנן שבע מצות נצטוו בני נח דינין וברכת

השם ע”ז גילוי עריות ושפיכות דמים וגזל ואבר מן החי

Our Rabbis taught: The b’nei Noah received seven commandments: [set up] courts of justice; to refrain from blasphemy, idolatry; sexual depravity; bloodshed; robbery; and eating flesh cut from a living animal. (Sanhedrin 56)

Yes, those are the same seven, more-or-less, as we saw in the Tosefta. But wait, there’s more!

תנו רבנן שבע מצות נצטוו בני נח דינין וברכת השם ע”ז

גילוי עריות ושפיכות דמים וגזל ואבר מן החי רבי חנניה בן (גמלא) אומר אף על הדם מן

החי רבי חידקא אומר אף על הסירוס רבי שמעון אומר אף על הכישוף רבי יוסי אומר כל

האמור בפרשת כישוף בן נח מוזהר עליו (דברים יח, י) לא ימצא בך מעביר בנו ובתו באש

קוסם קסמים מעונן ומנחש ומכשף וחובר חבר ושואל אוב וידעוני ודורש אל המתים וגו’

ובגלל התועבות האלה ה’ אלהיך מוריש אותם מפניך ולא ענש אלא אם כן הזהיר רבי אלעזר

אומר אף על הכלאים מותרין בני נח ללבוש כלאים ולזרוע כלאים ואין אסורין אלא בהרבעת

בהמה ובהרכבת האילן

R. Hanania b. Gamaliel said: Also not to partake of the blood drawn from a living animal. R. Hidka added emasculation. R. Simeon added sorcery. R. Yose said: The heathens were prohibited everything that is mentioned in the section on sorcery. For example: There shall not be found among you anyone who makes his son or daughter to pass through the fire, or that uses divination, or a fortune teller, or an enchanter, or a witch, or a charmer, or a consulter with ghosts, or a wizard, or a necromancer. For all that do these things are an abomination to the Lord: and because of these abominations the Lord your God does drive them [Canaanites] out from before you. R. Eleazar added the forbidden mixture in plants and animals: now, they are permitted to wear garments of mixed fabrics of wool and linen and sow diverse seeds together; they are forbidden only to hybridize heterogeneous animals and graft trees of different kinds.

How many now? You do the math, it’s beyond me!

Let us now move a few centuries ahead to the time of Moses Maimonides, familiarly known as “Rambam” in Jewish conversation. In hisencyclopedia of Jewish practice (halakhah), he writes:

משֶׁה רַבֵּנוּ לֹא הִנְחִיל הַתּוֹרָה וְהַמִּצְוֹת אֶלָּא

לְיִשְׂרָאֵל. שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר (דברים לג, ד) “מוֹרָשָׁה קְהִלַּת יַעֲקֹב”.

וּלְכָל הָרוֹצֶה לְהִתְגַּיֵּר מִשְּׁאָר הָאֻמּוֹת. שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר (במדבר טו, טו)

“כָּכֶם כַּגֵּר”. אֲבָל מִי שֶׁלֹּא רָצָה אֵין כּוֹפִין אוֹתוֹ לְקַבֵּל תּוֹרָה

וּמִצְוֹת. וְכֵן צִוָּה משֶׁה רַבֵּנוּ מִפִּי הַגְּבוּרָה לָכֹף אֶת כָּל בָּאֵי הָעוֹלָם

לְקַבֵּל מִצְוֹת שֶׁנִּצְטַוּוּ בְּנֵי נֹחַ. וְכָל מִי שֶׁלֹּא יְקַבֵּל יֵהָרֵג.

וְהַמְקַבֵּל אוֹתָם הוּא הַנִּקְרָא גֵּר תּוֹשָׁב בְּכָל מָקוֹם. וְצָרִיךְ לְקַבֵּל

עָלָיו בִּפְנֵי שְׁלֹשָׁה חֲבֵרִים. וְכָל הַמְקַבֵּל עָלָיו לָמוּל וְעָבְרוּ עָלָיו

שְׁנֵים עָשָׂר חֹדֶשׁ וְלֹא מָל הֲרֵי זֶה כְּמִן הָאֻמּוֹת:

Moses our Teacher did not bequeath the Torah and the Commandments to anyone but to Israel, as it says, “the Heritage of the Congregation of Jacob” (Deut. 33:4), and to anyone from the other nations who

wishes to convert, as it says, “as you, as a convert” (Numbers 15:15). However, no one who does not want to convert is forced to accept the Torah and the commandments. Moses our Teacher was commanded by the Almighty to compel the world to accept the commandments of the b’nei No’ah. Anyone who fails to accept them is executed. Anyone who does accept them upon himself is called a resident alien [or: convert] who may reside anywhere. He must accept them in front of three wise and learned Jews. However, anyone who agrees to be circumcised and twelve months have past and he was not as yet circumcised is no different than any other member of the nations of the world. [Rambam, Yad, Melakhim, 8:10]

Before I comment on this, we should also look at a similar situation which is found two short chapters later:

שְׁנֵי עַכּוּ”ם שֶׁבָּאוּ לְפָנֶיךָ לָדוּן בְּדִינֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל

וְרָצוּ שְׁנֵיהֶן לָדוּן דִּין תּוֹרָה דָּנִין. הָאֶחָד רוֹצֶה וְהָאֶחָד אֵינוֹ

רוֹצֶה אֵין כּוֹפִין אוֹתוֹ לָדוּן אֶלָּא בְּדִינֵיהֶן. הָיָה יִשְׂרָאֵל וְעַכּוּ”ם

אִם יֵשׁ זְכוּת לְיִשְׂרָאֵל בְּדִינֵיהֶן דָּנִין לוֹ בְּדִינֵיהֶם. וְאוֹמְרִים לוֹ

כָּךְ דִּינֵיכֶם. וְאִם יֵשׁ זְכוּת לְיִשְׂרָאֵל בְּדִינֵינוּ דָּנִין לוֹ דִּין תּוֹרָה

וְאוֹמְרִים לוֹ כָּךְ דִּינֵינוּ.

As to two idolators [perhaps meaning non-Jews] appearing before you to be judged in accordance with laws of Israel and wishing to be judged in accordance with the Torah, we do so. If one wishes to be judged so and the other not, he is not compelled to be judged except by their own laws. If an Israelite and an idolator appear before us and we can decide in favor of the Israelite in accordance with their laws, we judge them in

accordance with their laws and we say to him, ‘this is your law’. But if the Israelite has merit in accordance with our Law, we judge him by Torah Law and tell him ‘This is our Law’.

וְיֵרָאֶה לִי שֶׁאֵין עוֹשִׂין כֵּן לְגֵר תּוֹשָׁב אֶלָּא

לְעוֹלָם דָּנִין לוֹ בְּדִינֵיהֶם. וְכֵן יֵרָאֶה לִי שֶׁנּוֹהֲגִין עִם גֵּרֵי תּוֹשָׁב

בְּדֶרֶךְ אֶרֶץ וּגְמִילוּת חֲסָדִים כְּיִשְׂרָאֵל. שֶׁהֲרֵי אָנוּ מְצֻוִּין

לְהַחֲיוֹתָן שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר (דברים יד, כא) “לַגֵּר אֲשֶׁר בִּשְׁעָרֶיךָ תִּתְּנֶנָּה

וַאֲכָלָהּ”.

It seems to me that we do not do this with a ger toshav [resident alien, sometimes translated as a

potential convert], but we always judge him by his own laws. And it also seems to me that we treat gerei toshav with respect and consideration, as we would an Israelite. Recall that we are required to keep sustain him, as it says, “to the stranger who is within your gates you shall give it [meat that Israelites

may not consume], that he may eat.” [Deut. 14:21].

From this discussion, it is clear that Maimonides is using the term b’nei No’ah differently from the other sources we have examined. Here, b’nei No’ah are not all non-Israelites,

but rather the special class of people who are in the process of or have already accepted membership in the community of Israel. Until now, we have imagined that there are two kinds of people: Israelites and non-Israelites. But in the view of the Rambam, there are three: Israelites, non-Israelites, and b’nei No’ah. The existence of a kind of middle group provides reasons for explaining certain principles of the administration of the courts of justice.

We have seen the evolution of a concept, changing and evolving with the circumstances in which Israelites and Jews have foundthemselves over thousands of years. We have only touched on many of the ideas which describe how different generations viewed the need to consider the proper way that nations should interact with one another. Maimonides continues in a way that is so fitting for all of us:

וְזֶה שֶׁאָמְרוּ חֲכָמִים אֵין כּוֹפְלִין לָהֶן שָׁלוֹם

בְּעַכּוּ”ם לֹא בְּגֵר תּוֹשָׁב. אֲפִלּוּ הָעַכּוּ”ם צִוּוּ חֲכָמִים לְבַקֵּר חוֹלֵיהֶם

וְלִקְבֹּר מֵתֵיהֶם עִם מֵתֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וּלְפַרְנֵס עֲנִיֵּיהֶם בִּכְלַל עֲנִיֵּי

יִשְׂרָאֵל מִפְּנֵי דַּרְכֵי שָׁלוֹם. הֲרֵי נֶאֱמַר (תהילים קמה, ט) “טוֹב ה’

לַכּל וְרַחֲמָיו עַל כָּל מַעֲשָׂיו”. וְנֶאֱמַר (משלי ג, יז) “דְּרָכֶיהָ

דַרְכֵי נֹעַם וְכָל נְתִיבוֹתֶיהָ שָׁלוֹם”:

Our Sages have said “We do not double our greeting, “Shalom” [in other words, we do not say, “Shalom, Shalom!”]. This refers to the idolators, but we do so with a ger toshav [resident alien]. But note that even with regard to idolators, our Sages have commanded us to visit their sick and bury their dead along with Jewish dead and sustain their poor along with the poor of Israel is for the “sake of peace.”

In other words, while some reservation must be made for our relationship to someone who does not honor God, nevertheless, we are obligated to treat them all with common decency.

And he concludes in a way that is so appropriate to our honoring Aryeh Seagull, “We act charitably to all as the Psalmist says, “God is good to all, and God’s compassion is expressed in all God’s

works.” [Psalms 145:9] And Proverbs says [3:17],

“Her ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her pathways lead to peace.”

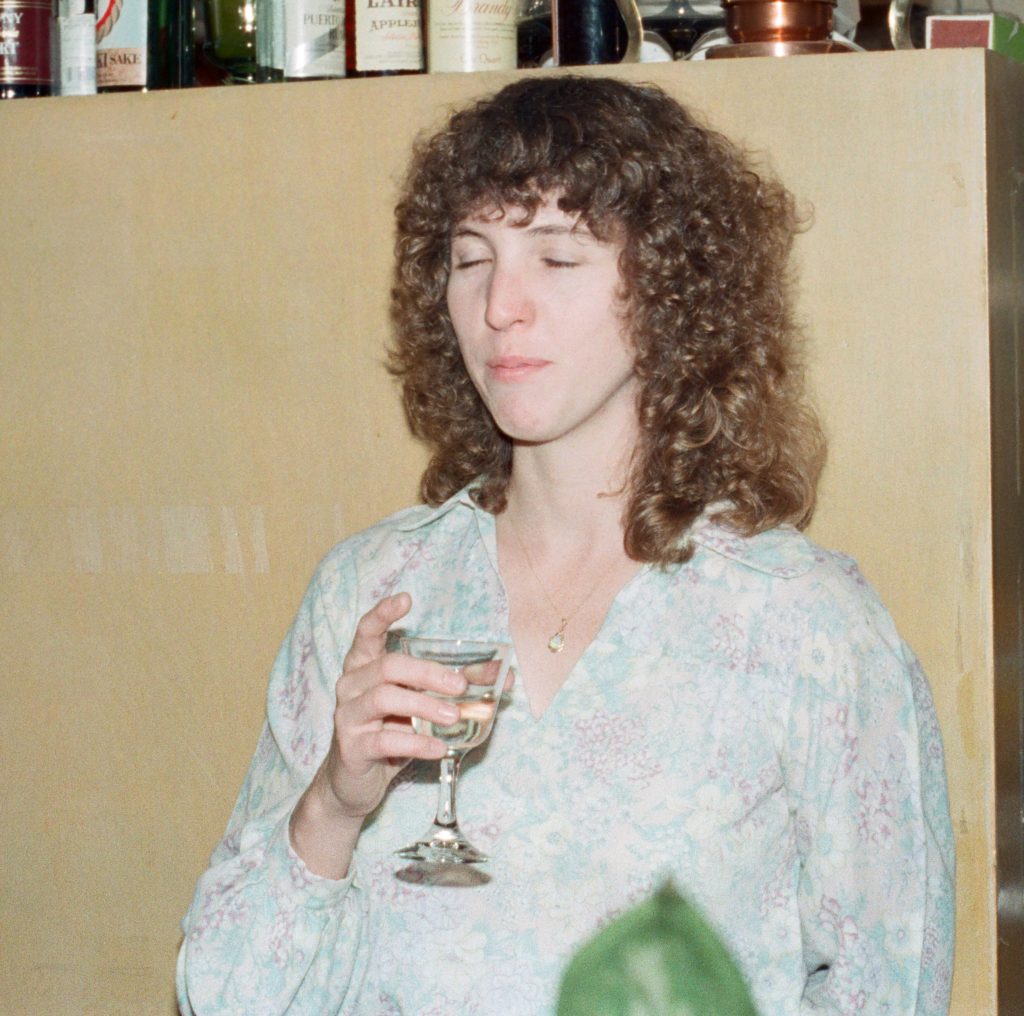

Aryeh with his beautiful bride, Elizabeth

[1] Biblical quotations are adapted from several versions, mostly the New Jewish Publication Society, with some emendation by me.